Around 19% of people in the UK have an impairment but exercise in this population is very low. Less than a quarter of people with multiple sclerosis regularly exercise and over 30% of people with MS are overweight. Only 13% of disabled children meet the daily exercise recommendations; that’s 87% of children with a disability who are not exercising enough.

So why are they not exercising?

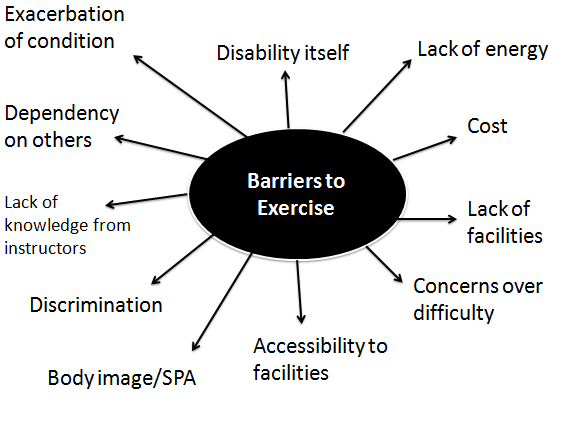

Firstly, there are issues relating to the facility itself; is the facility accessible and inclusive? Does it have any inclusive equipment? Are the staff knowledgeable and welcoming? Sometimes the disability itself can be a barrier as people believe exercise will be too difficult for them, others will discriminate against them, their condition may be exacerbated by physical activity or they will be too tired, or they simply cannot engage in exercise. Finally, body image also acts as a barrier to exercise.

Body image is your attitude towards your own body; how you see yourself, how you think and feel about the way you look, and how you think others perceive you. Poor body image is linked to social physique anxiety; people who are obese and have social physique anxiety can be scared to enter a gym environment due to how their body might be perceived by others, and how they themselves see their body. For people with disabilities, particularly visible ones like amputations, social physique anxiety can prevent them from exercising. Breakey (1997) found a correlation between positive body image and psychological well being in people with amputations – these individuals had lower levels of anxiety and depression, and higher levels of life satisfaction. Atherton and Robertson (2006) found that negative appearance related beliefs towards amputations contributed to distress and adjustment difficulties. Interestingly, although body image is correlated to levels of activity, people with an amputation display high levels of social physique anxiety; that is to say although exercise will benefit their body image, there is an initial fear to engage in exercise due to lack of confidence. The research on this area is sparse; it could be that this is a population that would experience more social physique anxiety due to scarring, stumps, and prosthetics, yet it’s not really been thoroughly looked into. The goal of rehabilitation following an amputation is to get the individual mobile and self-dependent, often through resistance training and physiotherapy, but not focused on regular exercise programme.

Another great, but under performed, activity is Tai Chi. It’s a martial art but not a typical combat one. It involves balance and shifting weight between the legs which makes it excellent for elderly people because the focus is on improving balance. It is also a low demand activity involving slow, flowing movements – perfect for people who currently do not exercise, or are unable to exert themselves too much. It can be adapted for people in wheelchairs, and can settle people who are perhaps restless in retirement. Tai Chi can also reduce the number of falls in this population too.

Another great, but under performed, activity is Tai Chi. It’s a martial art but not a typical combat one. It involves balance and shifting weight between the legs which makes it excellent for elderly people because the focus is on improving balance. It is also a low demand activity involving slow, flowing movements – perfect for people who currently do not exercise, or are unable to exert themselves too much. It can be adapted for people in wheelchairs, and can settle people who are perhaps restless in retirement. Tai Chi can also reduce the number of falls in this population too.