My previous post touched upon the transition from being a youth superstar to being painfully average in an elite sporting world though without much science behind it. This transition hasn’t really received adequate investigation and it’s worth looking at, particularly as it differs between sports. Generally in the football system of the UK, you work your way up the youth ranks, maybe playing the occasional senior game in the league cup, and seems to be much more of a gradual introduction to senior levels. This is contrasted to the NHL which holds a yearly draft where draft eligible players are picked by teams each round, and if you make training camp then welcome to the NHL kid. Each year, there’s a whole wave of rookies, most of them fresh faced 18 year olds, but not always – as Artemi Panarin is making sure people know.

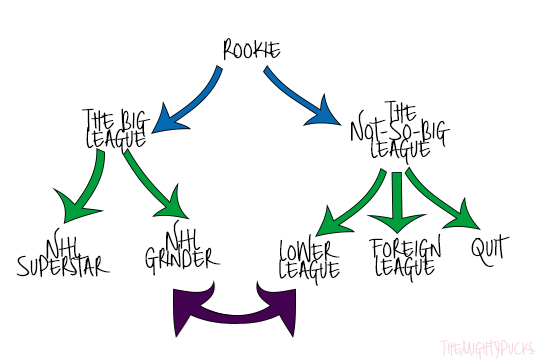

From a hockey perspective, making the draft doesn’t mean you’re automatically in the NHL. You gotta work, kid. This year’s draftees, Eichel, McDavid, and Larkin are certainly making waves, but not every rookie is destined to be “the next Gretzky”. It’s not NHL or bust. You might play a game or two then be sent down to the team’s affiliate; you might flit between the two for some time. You might be placed on waivers and hope that another team picks you up. You could move abroad. Football might dominate Europe but the ice hockey league in the UK is dotted with North American players. Or you could throw that dream away and settle for a normal life. These decisions conjure up more issues – assimilating into a new culture*, anxiety over when/where your next game will be, or adjusting to a life where playing is given a back seat.

Bruner, Munroe-Chandler, and Spink (2007) explain that young players transitioning into elite sport levels experience issues both on and off the ice, including personal development and performance. Confidence is a fine line; you’re playing on the same ice as Pavel Datsyuk and mustn’t get star struck, after all you’re in this league now too. Can a rookie ever be too confident? Or can the fame get too much? Certainly, the Boston Bruins were willing to trade their 2nd overall draft pick and Stanley Cup winner Tyler Seguin due to his -alleged- hard partying. It’s understandable. You’re a young, attractive, professional athlete and your team mates have already begun to settle down and start families. It can be lonely. Young players tend to flock together and become roommates on the road and at home, or veteran players take in a rookie to their family homes.

The veteran-rookie relationship is fantastic. Crosby lived with Mario Lemieux for a good few seasons whilst he adjusted to life in Pittsburgh as Sid the Kid; Evgeni Malkin lived with fellow countryman, Sergei Gonchar. Rookies are provided with a good example to follow, on the ice and off the ice. In some instances, they’ve acquired new brothers and sisters. Maybe they’re less likely to party if they’ve got a second set of parents to come home to. Maybe they’ll feel less lonely – the NHL schedule is tough and can be hard to find friends away from the ice when you’re so often on the road. Maybe they’ll actually eat decent meals! For foreign players, it can ease the transition to a new culture and allow them to speak their native language, helping to curb some home sickness. Comparing the transition of rookies who live alone versus living with other players as they transition into elite sports is definitely an area that needs examining.

* That’s not to say that rookies don’t have a culture shock when they join the NHL – you’re 18 years old, living away from home, and a pro athlete, you’re hot s***! And of course players from overseas must adjust to a new life in North America, however many play in a junior hockey league there before the draft, such as Landeskog or Nestrasil.