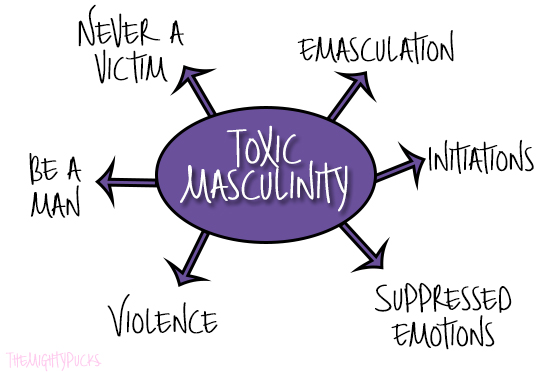

This post will focus on toxic masculinity which has become a bit of a buzzword for feminists, but it is an important topic that needs addressing. It holds that imposing masculinity on men can be harmful, particularly as the typical masculine gender role is one associated with violence, assertiveness, independence, and non-emotional. There are several facets to the concept of toxic masculinity which will be explored through the series of these posts.

To understand toxic masculinity in a sporting context, firstly we ought to examine how these gender stereotypes begin to influence from birth. Masculinity is difficult to define and measure, furthermore cross-cultural differences also play a role therefore this will focus on the westernized view of ‘being a man’. Just as femininity encourages women to be thin, beautiful, and motherly, masculinity commands that men be an unattainable ideal of an emotionally-stunted invincible hero. Both are unrealistic and damaging. In a study by Smith and Lloyd (1978), new mothers played with an actor baby who was presented as either male or female and dressed in gender typical clothes (i.e. in pink when ‘a girl’). Results showed that when the child was believed to be male, the women engaged in more physical play, encouraged gross motor activity, and reached for the “male” toys. Girl’s toys are usually pink, dolls, or miniature kitchens, whereas boys toys have wheels, are weapons, or sports related. Another study has shown that men handle a baby less than women – perhaps as boys are discouraged from playing with dolls and girls are praised for being maternal. An important finding was that the majority guessed the child was male due to physical and behavioral indicators like being strong – the child in the study was actually female. The scariest thing is that this happens from birth; Rubin, Provenzano, and Luria (1974) showed that although there were no significant physical differences between newborns, parents already described the girls as little, cute, and pretty – these babies were 24 hours old! (No offense to the new parents out there, but newborns fresh from the womb are anything but pretty).

Boys are more likely to receive physical punishments than girls. I don’t believe for a moment that boys are naughtier than girls, however boys are allowed to be more boisterous – it’s not ladylike to fight, when boys are physically aggressive, well it’s just boys being boys. I wonder if any gentlemen reading this have been told that boys don’t cry? Girls are allowed to cry, girls are allowed to seek comfort when they’re hurting, but boys? Big boys don’t cry.

This leads in nicely to one part of toxic masculinity which is emotional suppression. When you tell a boy that he shouldn’t cry, that he shouldn’t seek comfort when he’s hurting, you are damaging his emotional responses. Boys are consistently comforted less than girls and told to control their emotions. An inability to recognise and respond to emotions can have serious adverse effects for a man, such as repressing emotions or externalising them through destructive behaviours. Although women are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder, mean are four times more likely to commit suicide. One has to wonder whether 1) men are not seeking help hence the under-representation of mental disorders in this population 2) this reluctance is, in part, due to their socialisation that expressing emotions is a weakness. Mental health struggles are not a sign of weakness.

A professional sporting environment is a hub of hyper-masculinity. In a sport like hockey where a fist fight on the ice is part of your run-of-the-mill day, it’s easy to see why men are reluctant to come forwards and discuss their emotions. Nobody wants to be called a pussy. In November 2009, German footballer Robert Enke committed suicide by standing in front of a train. Following his death, his wife confirmed that he had struggled with depression for several years, and recently had difficulty coping with the pressure of being a professional footballer and the death of his daughter. In August 2011, ice hockey player Rick Rypien committed suicide. He had battled depression for a decade or more. Rick was considered small for NHL standards, but never shied away from a fight (if you’re suffering from depression and society tells you it’s a weakness, one way to show them you’re not is by throwing punches).

He played the game with such reckless abandon and a fearlessness. He had cuts and bruises and nicks on his face, it seemed like a new one every night.

The NHL has made steps to raise awareness of mental health and Rypien’s close friend, Kevin Bieksa, has played a pivotal role in tackling attitudes towards mental illness. The Bell Let’s Talk campaign is also a positive step with many players lending their voice to it. Robert’s widow, Teresa, works with the German FA and Hannover 96 to promote awareness and remove the stigma attached to mental health. It can be a big step for men to acknowledge that they need help – Enke was asked by the team’s sport psychologist if he was suffering from depression and denied it – so Teresa makes a great point:

We don’t want sports people to go public and say we have depression. There’s no need to communicate it publicly. The help should be given internally. The coaches and the teams should help and support the player and let them know they can come back from it.

Breaking down these barriers in a sports environment is a positive sign, but is important to recognise that from a young age the masculine ideal of being strong and silent can be damaging and is often reinforced. The steps ought to be taken earlier; information on mental health should be made readily available from a youth level, including how to seek help, because even young people commit suicide.

If you have been affected by any of the subjects raised in this post then please don’t hesitate to reach out for help.